Whitmer subsidy record: Companies get $1 billion; jobs fall short of promises

- Since Whitmer took office in 2019, Michigan has paid $995 million in subsidies to firms that have created 13,079 jobs

- That’s one-fifth of the jobs promised, and the public often isn’t told what happens to deals after they are announced

- Bridge had to compile a database of hundreds of pages of state records to trace the state’s return on investment

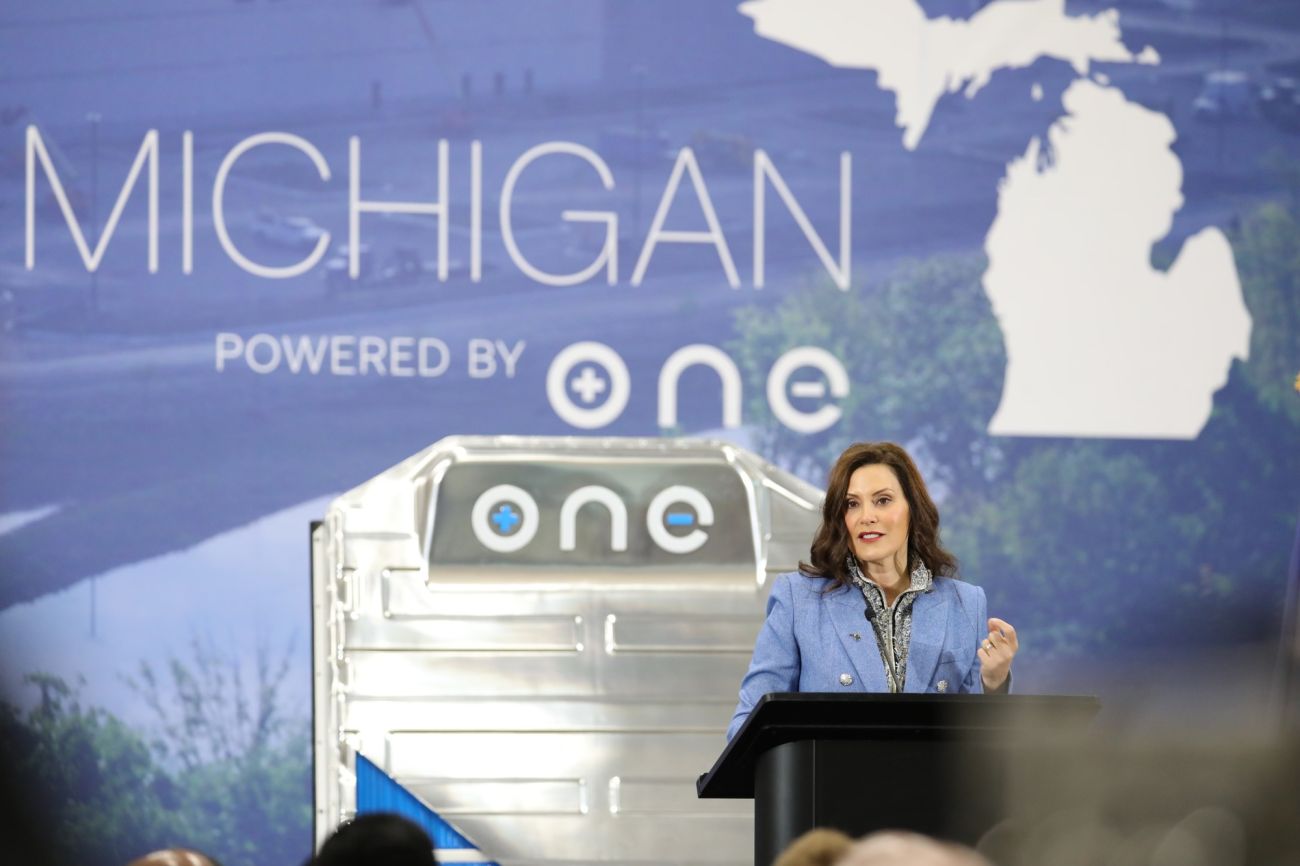

Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has spent nearly $1 billion on corporate incentives since taking office, creating a fraction of the jobs and investment she promised, according to a Bridge Michigan analysis of hundreds of pages of public records.

Through six years of her administration, Michigan has given $995 million in taxpayer money to 102 companies. They have created 13,079 jobs, a cost per job of $76,076, records show.

That’s five times fewer the number of jobs Michigan was supposed to receive from 300-plus companies awarded incentives since Whitmer became governor.

All told, the state has pumped hundreds of millions of dollars into 54 projects that, so far, have yet to create a single job, according to the most recent state reports.

“If the goal is to prosper, I don't think there's any evidence that (corporate incentives are) a good strategy,” said Lou Glazer, president of Michigan Future Inc., a nonpartisan think tank focused on state success.

“The number of jobs involved are just too small.”

Corporate subsidies under Whitmer

Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has dramatically expanded corporate subsidies since she took office, but many of the deals have shrunk since they were announced. Here’s a look at what Michigan promised and what was delivered from 2019 to 2024.

Original agreements

$2.46 billion in incentives to

340 companies for

$35 billion in investments and

65,491 jobs, at a cost of

$37,562 per job.

Outcome so far

$995 million spent by Michigan to

102 companies, that invested

$12.3 billion and created

13,079 jobs, at a cost of

$76,076 per job

The tallies are

64% less for business investments and

22% of the total jobs promised, according to state reports

Bridge’s analysis is the first public accounting of its kind on Michigan’s return on investment in job-growth subsidies under Whitmer’s entire term. She argues the incentives are necessary, but lawmakers in both parties are increasingly questioning them.

The analysis revealed that deals are often revised and downsized, long after public statements from Whitmer announcing the “promise” or “addition” of jobs.

Since 2019, Michigan has pledged $2.46 billion to 340 companies through five subsidy programs. In return, the firms promised to create 65,000 jobs, according to a database created by Bridge of public documents available from the Michigan Economic Development Corporation (MEDC), and its public spending arm, the Michigan Strategic Fund.

Until Bridge’s analysis, however, the public was never given a complete picture of the overall performance of incentives throughout Whitmer’s term.

The Michigan Economic Development Corp. maintains a transparency page on its website and produces reports to the Legislature. The reports reflect only that fiscal year, but not a comprehensive accounting of past awards, jobs promises or actual hiring.

Taxpayers deserve better, several legislators told Bridge.

“They don't hear the final story as much as they heard the rainbows and butterflies at the beginning,” said Rep. Steve Carra, R-Three Rivers and chair of the new House subcommittee on incentives.

Lawmakers need the tools to “accurately assess if the way that we are spending taxpayer dollars is actually resulting in a return on that investment,” said state Sen. Mallory McMorrow, D-Royal Oak, who is running for US Senate.

“What we're seeing right now does not always give us the ability to see that.”

The governor did not respond to inquiries from Bridge about its findings. Speaking earlier this year, she called the subsidies a success.

"As you look at the investment that we've been able to land in Michigan, from incumbent Michigan businesses of all sizes or others who are looking to come to Michigan, we've had some good victories,” she told Bridge in February.

Typically, deals are written to give companies two to 12 years to meet benchmarks. MEDC spokesperson Otie McKinley said large projects take years to develop but are making good progress.

Behind the subsidy curtain

Bridge used six years’ worth of strategic fund meeting documents and MEDC annual reports to the Legislature to construct a database to gauge the state’s return on investment through five major job-growth subsidy plans.

The data is through the most recent state reports.

Bridge’s analysis found:

- The median pay for jobs supported by subsidies is roughly $60,000, about what the average worker makes statewide.

- Taxpayers aren’t able to discern exactly how much the jobs pay on average because Michigan does not require companies to report wages after receiving incentives. Just over a third, 35% of firms, voluntarily reported wages. That is how Bridge arrived at its calculation.

- Actual job creation is 22% of what was promised, after Bridge excluded a few dozen deals for which the state offers no hiring data. They include companies inking deals in the fourth quarter of 2024 and those promising a combined 3,067 jobs in exchange for state money to cover worker training.

- About 200 companies that are in line for subsidies reported creating no jobs. They include eight of the biggest jobs deals announced.

- Total state spending on incentives since Whitmer took office easily exceeds $1 billion. Bridge’s figure does not include another $387 million in tax breaks. Companies also received millions of dollars more in infrastructure upgrades.

- Even if all of the jobs promised during Whitmer’s time as Michigan’s top elected official were realized, the number of jobs in the state would increase by less than 2%.

The findings should prompt debate, Glazer said. It’s notable that the state’s return on investment is only 1 in 5 of the promised jobs, he said.

“But the larger debate we need to be having is, even if it was 5 out of 5 of them, is whether that’s a good use of the money,” he asked.

“That's the debate we've never had in Michigan.”

To be sure, Whitmer’s time in office has been shaped by the pandemic, which upended the economy and stalled many projects. In the four years before she took office, private sector jobs grew 6.3% to about 3.9 million, then slowed 0.28% during her first year as governor in 2019.

The state lost 10% of its private-sector jobs — 370,100 — during the pandemic before recovering in 2023. Overall, non-government jobs in Michigan have grown 1% during Whitmer’s tenure.

Subsidized jobs represent 32% of the state’s new jobs during that time, according to Bridge’s analysis.

Overall, incentives have proven “a failure,” said Rep. Jay DeBoyer, chair of the House Oversight Committee.

The largest deals “have consistently, overwhelmingly, never met the expectation that we were promised,” said DeBoyer, R-Clay.

Subsidies spike amid EV rush

Like other states, Michigan has used corporate incentives for years, but they increased dramatically after Ford Motor Co. in 2021 announced an $11.4 billion electric vehicle plant expansion in Kentucky and Tennessee.

That created urgency in Michigan for more tools to lure large-scale projects and help retain its signature industry, automobiles. Whitmer worked with lawmakers in both parties to create the $2 billion Strategic Outreach and Reserve (SOAR) Fund to compete for big projects.

Adding to the fears were several reports during Whitmer’s administration that Michigan is losing ground to other states. Income rankings fell to 39th and set a new low in 2024. Michigan also gets middling marks from business groups for growth and prosperity.

Business leaders support economic development incentives, including the Michigan Manufacturers Association and the Detroit Regional Chamber. Both cite competitive pressures from other states that use subsidies to lure businesses.

“Michigan is behind the curve in attracting new, next-gen industry,” said Sandy Baruah, CEO of the chamber.

Overall, Baruah gives Michigan a “B” grade for its use of subsidies.

“Michigan has a history of being super inconsistent regarding economic development approaches, and that's a killer,” he said. “Consistency and reliability are more important than the policies themselves.”

Related:

- After $1B and mixed results, Michigan lawmakers cooling on corporate incentives

- Top 10 subsidies under Whitmer: Michigan spends $900M; firms create 4,200 jobs

- Corporate subsidies cost Michigan $335M; 40% of deals create low-paying jobs

- Michigan has spent $1B on EV, battery plants. So far, they’ve created 200 jobs

- With Flint megasite deal, Michigan tops $1B in spending on development land

Quentin Messer, Jr., CEO of the state’s Economic Development Corp., said Michigan subsidies “are going to be critically important if we as Michigan are going to rise among the 50 states.”

“We need to make sure that we have the tools,” he told the Michigan House Committee on Economic Competitiveness on March 13.

Traditionally, Michigan is not listed among states with “meaningful” job creation incentives. Kentucky, Tennessee and Alabama offer steep tax breaks, while North Carolina, Ohio and South Carolina allow businesses to keep revenues from state taxes levied on new employees.

“We must stay nimble to support businesses that are already here and win new ones, too,” Whitmer said in January at the Detroit auto show. “I know securing these big factories hasn't always been easy, but we’ve got to keep looking at it.

“We can't just unilaterally disarm like some on the far left and far right would have us do.”

Still, critics question how much of a role subsidies actually played in the 40,600 private jobs gained during Whitmer’s tenure.

“The reality is that, overwhelmingly, these companies would be building the exact same thing and hiring the same people without the subsidy, because it makes business sense to do that,” said John Mozena, president of the Center for Economic Accountability, a Michigan-based group that advocates for government transparency and reform.

“Very, very few deals truly only make business sense because of the subsidy.”

Bridge’s analysis comes amid debate about the future of incentives in Michigan.

Last year, Whitmer’s fellow Democrats proposed $500 million in the next budget year to fund mega projects and $2.5 billion over 10 years to maintain large-scale incentives while broadening impact to transit and housing.

Republicans, now the majority party in the House, propose eliminating the largest subsidies, including the SOAR Fund, unless funding shifts from taxpayers. Leadership also initiated subcommittees to the House Oversight Committee, including the one led by Carra targeting corporate subsidies.

The debate about incentives is likely to escalate in Lansing during the budget process that starts in a few weeks.

Subsidy complexity

Bridge’s investigation found that deals are often downsized in private months and sometimes years after public pronouncements of the deals.

On Oct. 6, 2022, for instance, Whitmer hailed a proposed investment of $1.6 billion from two EV battery initiatives, Gotion Inc. near Big Rapids and Our Next Energy in western Wayne County.

The deals were supposed to create 4,462 jobs, in exchange for nearly $400 million in subsidies plus tax breaks.

“Since I took office, we have announced over 30,000 good-paying auto jobs including major investments from the Big Three and projects building electric vehicles, batteries, and semiconductor chips in Michigan, supporting critical supply chains,” she said in the statement.

The 30,000 figure trumpeted by Whitmer, however, was already inaccurate, since many deals with companies receiving subsidies had already been amended.

At a glance

Michigan created the Strategic Operating and Attraction Reserve in 2022 to lure mega projects to the state, particularly electric vehicle battery plants. Here’s a look at how the investment is shaping up:

What was promised

$1.8 billion to

9 companies to invest

$17.5 billion and create

14,779 jobs

What was delivered

$889,226,835 to

5 companies that invested

$2.3 billion and created

0 jobs

After announcing that GM would create 4,000 jobs in exchange for subsidies in Lake Orion and Delta Township, the state later contracted with the automaker to create just 3,200 jobs.

It was a similar story at AKASOL, a battery maker that received $2.24 million to create 224 jobs in Hazel Park in Oakland County in 2019.

Two months before Whitmer touted the 30,000 EV jobs, AKASOL and the state agreed to amend its agreement and trim its incentive to $900,000 to create 90 jobs.

The company had until March 2023 to do so. Instead of meeting the deadline, AKASOL, a division of BorgWarner, this summer will close the factory and another in Warren, laying off 188 workers.

The company, having met its updated requirement, gets to keep the taxpayer subsidy, the MEDC’s McKinley told Mlive.com.

Critics of incentives are frustrated that MEDC reports about the incentives are often six months old by the time they are made public. Changes are listed annually not cumulatively, critics add, making it difficult to gain a full understanding of job progress.

Last year, deals with 46 companies were terminated or money was clawed back when job promises failed to materialize.

Some companies more quietly pause their expansions, like Nel Hydrogen, which accepted a $10 million subsidy for creating over 500 jobs. Development is on hold, but the state’s deal remains open. Several EV-battery related deals — the largest and most expensive — received extensions on their job-delivery deadlines

Meanwhile, since October 2019, amendments to signed contracts included five companies that increased job outlooks and dollar values, adding a combined 1,269 projected jobs to their deals and gaining $7.7 million in state funding.

Eighteen companies reduced their total projected jobs by a combined 1,825. And companies receiving incentives returned just under $1 million to the state in 2024 under “clawback” provisions.

“Economic development reporting should not just be about what we've offered companies, but what they've actually done and what that cost taxpayers,” said James Hohman, director of fiscal policy for the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a free-market think tank in Midland.

“You just can't get an easy assessment from state reporting on those basic questions.”

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!