School offers peek at 'science of reading.' Can it boost scores in Michigan?

- Stockbridge Community Schools elementary teachers are among the first in the state to embrace literacy strategies that are part of a growing movement

- The schools are using practices sometimes referred to as the ‘science of reading’

- More Michigan schools will make changes in the coming years to comply with new laws aimed to improve literacy instruction

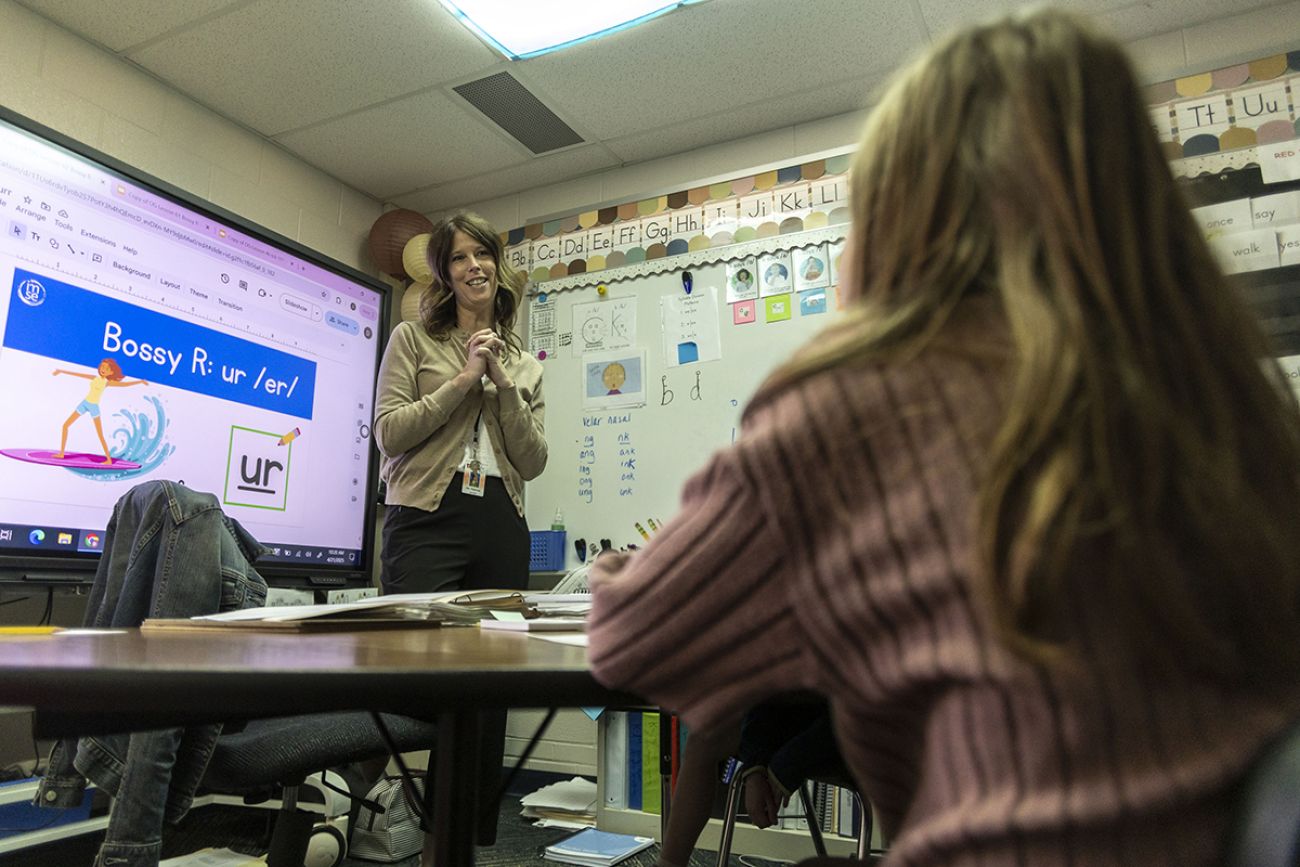

STOCKBRIDGE — In a first grade classroom in Stockbridge, 18 students sit on a rug while they say out loud the sounds different letter combinations make.

They shout together the sounds of “sm-,” “-xt,” “-lk,” “-nch,” as teacher Brittany Floyd stands in front of a colorful whiteboard, rehearsing with them. Soon, they’ll be back at their desks practicing sounds with sand.

It’s part of Floyd’s literacy lesson for the day.

This is the school’s first year where classroom-wide instruction, small group instruction and one-on-one tutoring are all using the same structured literacy strategies built on a growing academic movement known as the “science of reading.”

This means ensuring students know what different sounds letters and blends of letters make, understand why a given group of letters make a given sound and grasp the meaning of words and sentences they are saying out loud.

If it sounds technical, it’s because it is. If it sounds like it takes a lot of work, that’s true too.

The district is changing its literacy practices and could serve as a model for other districts as districts gear up to comply with reading reforms that go into effect with the 2027-2028 school year. These changes include ensuring schools identify students who have characteristics of dyslexia and providing them instruction in an evidence-based way.

“It’s not a fad, it’s not just phonics, it is not a pendulum swing,” said Kim St. Martin, a director at the Michigan Department of Education.

Instead, students work on their word recognition, language comprehension, vocabulary, topic and background knowledge so that they can “extract the meaning from written text and they can do so with ease,” she said.

Related:

- Studies raise warnings about Michigan child care access, cost

- DOGE cuts hit Michigan youth programs, reading initiative

- Fact check: Michigan schools are struggling. Can these ideas help fix them?

St. Martin’s works to help schools support students in large, small and one-on-one settings.

As Michigan third and fourth grade reading scores continue to be lower than before the pandemic, Michigan leaders are taking steps to change how literacy is taught in schools. But it’s a massive undertaking.

State leaders have embraced the science of reading by passing laws designed to support students with characteristics of dyslexia. They have also invested in teacher training, and aimed to make it easier for schools to understand what literacy curriculum has been proven to show results.

The scope of the problem

Only 39.6% of third graders were proficient or higher in English language arts in the 2024 Michigan Student Test of Educational Progress (M-STEP) tests. In Stockbridge, 35.2% of third graders were proficient or higher in ELA.

On the National Assessment of Educational Progress, also known as the NAEP or the Nation’s Report Card, 31 states scored higher in fourth-grade reading than Michigan, which was tied, statistically, with 18 states, according to NAEP.

Adrea Truckenmiller, an associate professor of special education at Michigan State University, told Bridge that science of reading is about using instructional practices that have been "rigorously studied and shown to work.”

She said she previously trained reading coaches in Mississippi on how to give feedback to teachers on reading instruction. The Southern state has made strides in the NAEP scores and science of reading practices are often cited as the reason why.

But the science of reading also comes with challenges: teachers often need to be re-trained, districts sometimes have to purchase new curriculum and getting people to all row in the same direction takes staff buy-in.

Giving teachers the tools

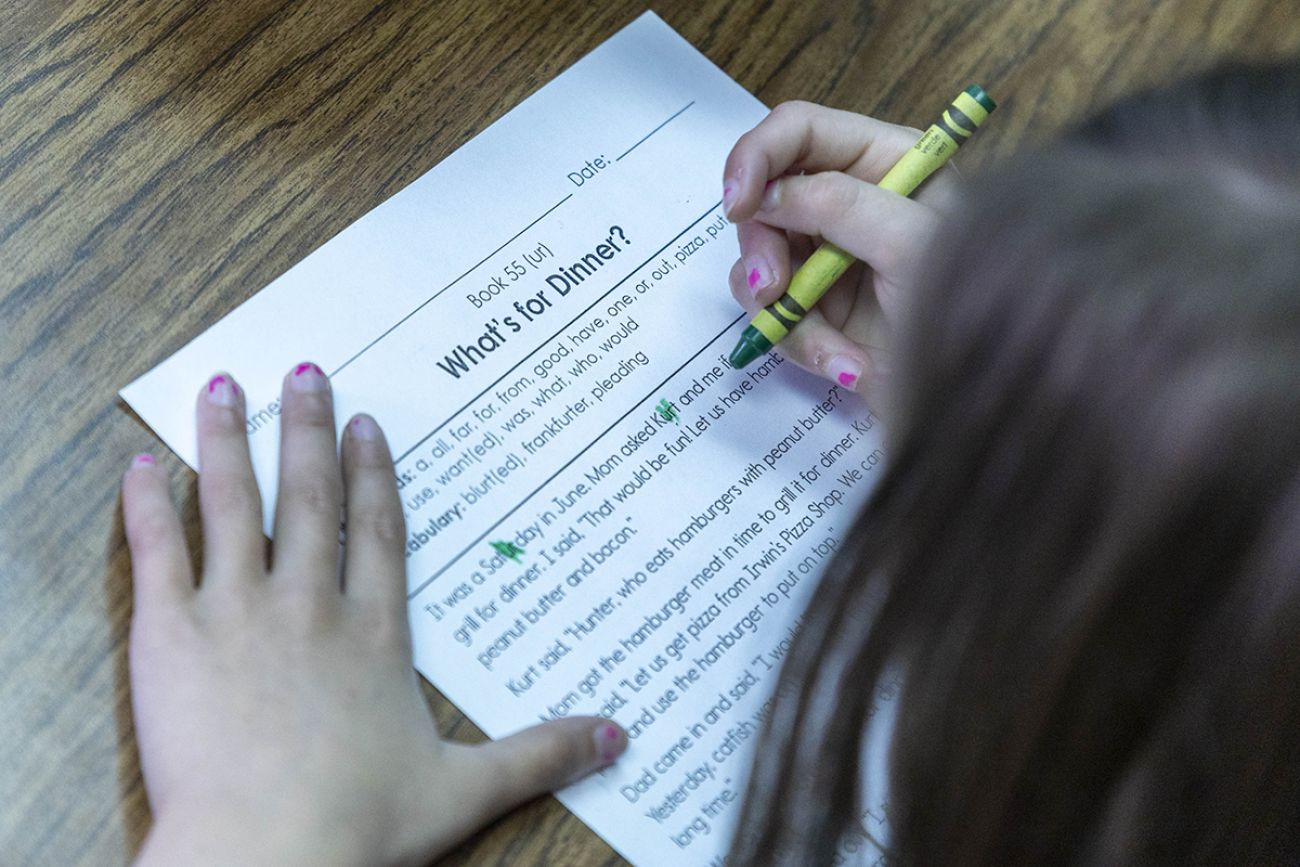

In the classroom, Floyd alternates between prompting students to say different letter combination sounds while sitting on a blue rug with smiley faces. Then, students draw combinations in sand trays. Students go back to the rug before returning to their desks for an activity where they are told a word and try to spell it out.

“It’s very explicit and repetitive, it is very straightforward, also very visual, hands on,” Floyd told Bridge. “So in the past it was kind of ‘say the sound and then we’re going to read a story,’ whereas now we’re just spending so much more time working with words, and working with chunks of words, working with the phonics of words. And it’s very structured in the way that kids know what’s coming next.”

When Bridge described this lesson to Truckenmiller, the MSU professor, she said that’s exactly the type of instruction teachers should be doing.

There are multiple opportunities for a student to grasp the skills, she said.

“Change is hard for anyone, and it can be very emotional for teachers, especially when they've been using strategies that they (say), ‘oh, it's worked in the past.,’ which it has for up to 60 to 80% of the students, but it's that other population that we're really looking at,” said Stockbridge literacy coach Cindy Stacy.

Still, she said teachers are reporting positive results.

“In college before, it was ‘look at the context, look at the pictures, you know maybe skip some words and see if the sentence makes sense and then go back,’ whereas now it’s strictly like decoding and there’s a process to how to help those kids decode each word,” said Deb Wightman, a Title I teacher.

The school also works with Beyond Basics to provide one-on-one tutoring for students. Generally, students receive 50 minutes of instruction five days a week for eight weeks, said Veronica Reynolds, director of account management at Beyond Basics.

Stephen Keskes, executive director of grants and academic innovation for Stockbridge, made sure all pre-K through fifth grade teachers including special education teachers received training from the Institute for Multi-Sensory Education.l

“I was really intentional about thinking of this as a system because I don't want the kids to be confused,” Keskes told Bridge, referring to when students go between their main classroom teacher, small group instructor or special education teacher.

Keskes said the total cost to train 36 teachers was about $70,000 plus $40,000 to compensate teachers for their extra time or to pay substitute teachers. He said state literacy funds were “crucial.”

Keskes sees early signs of progress: there’s a 9.5% proficiency increase among kindergarten through fifth graders this spring compared to last, he said.

But he acknowledges there’s a lot of work left to be done. Next year, the district plans to pilot a few literacy curricula.

“There's no perfect curriculum materials out there,” Keskes said.

Plus, there are a lot of curricula.

During the 2022-2023 school year, elementary school teachers across the state reported using 444 different curriculum resources for English language arts, according to an analysis by MSU researchers.

The state budget includes $87 million for a committee to vet curricula and then schools can apply for funding to purchase high-quality curricula.

“The magic’s in the instruction and so we want to be as efficient and effective with our reading instruction as we can be,” said St. Martin, the MDE official.

In short, the state is trying to shift from education vendors driving decisions to research studies driving decisions, Truckenmiller said.

Across the country, states make changes

Education Week reports that 40 states and Washington, DC, have passed laws or policies related to teaching reading in an evidence-based way since 2013.

The new Michigan laws require schools to screen K-3 students on characteristics of dyslexia and provide evidence-based reading instruction. They also require that college preparations programs in the state train future teachers on dyslexia and ways to support students. These requirements must be completed by the 2027-2028 school year.

But some schools aren’t waiting to get started.

“We’ve been waiting on this for 10 years, like our kids can’t wait. There’s not enough time,” Keskes told lawmakers last year when they were considering the bills.

Other Michigan efforts to improve literacy

Under both Republican and Democratic leadership, Michigan has aimed to make reading reforms.

Lawmakers have provided funds for literacy training in elementary schools and for early literacy coaches at intermediate school districts.

Stephanie O’Dea, instructional systems director at the Michigan Association of Intermediate School Administrators, told Bridge the organization is seeing positive results from the literacy coaching.

Now, all 56 intermediate school districts are committed to sharing that student data so that the organization has a better understanding of just how much of a difference these coaches are making, O’Dea said.

Lawmakers also set aside money for teachers to undergo science of reading training, known as LETRS. Pre-K through sixth grade teachers, special education teachers, elementary and district-level administrators and literacy coaches are all eligible for the state grant, according to the training website.

But this training is time-intensive. The company that operates the training estimates it takes between 137.5 to 168 hours total.

As of early this month, there were 6,388 educators taking the LETRs training, according to MDE spokesperson Bob Wheaton. An additional 3,857 people have completed the training.

There are about 117,000 public school teachers across the state in all grade levels this school year, according to state counts.

In a letter to lawmakers, State Superintendent Michael Rice called for mandatory LETRS training for teachers who teach reading and spelling, more instructional time for students and lower class sizes for younger grades in high-poverty schools.

In the meantime, some districts are already making literacy changes. Truckenmiller, who also sits on the state curriculum committee, said she has seen positive science of reading efforts in Detroit Public Schools Community District, Lansing School District and Saginaw and Ingham intermediate school districts.

She and others cautioned that it will take years for literacy reforms to be fully implemented and for results to show.

John Severson, of the intermediate school district group, told Bridge he’s glad the state is investing further in literacy rather than taking a completely different approach than what his organization has already been working on for years.

“In education sometimes and even in communities, we start to go for the next shiny spot. And I would say ‘stay the course with this, keep building it out, keep training more people,’” Severson said.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!