Trump firings hit Great Lakes sea lamprey program, Michigan forestry workers

- Efforts to keep a notorious Great Lakes invader at bay could be imperiled by the Trump administration’s mass firing spree

- Sea lamprey nearly wiped out the Great Lakes fishery in the 1900s, and are only kept in check today through annual chemical treatments in hundreds of rivers

- Dozens of workers focused on lamprey control were among scores of Michigan federal workers fired without notice in the past week

Just months ago, Great Lakes fish advocates were celebrating victory in a decades-long campaign to save lake trout populations from extinction at the hands of invasive sea lamprey.

Now they fear that progress could slip away, as President Donald Trump’s vow to downsize the federal government threatens to derail efforts to keep lamprey at bay.

“Our program is now in very serious peril,” said Greg McClinchey, legislative affairs and policy director for the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, a binational body that oversees lamprey control efforts on both the US and Canadian sides of the lakes.

Over the weekend, 14 US Fish & Wildlife Service employees who implement the program — most if not all of them based in Ludington and Marquette — were fired in a nationwide purge that some have dubbed “The Valentine’s Day Massacre.”

On top of that, the agency has been forbidden from hiring dozens of seasonal workers needed to dose Great Lakes rivers with lamprey-killing chemicals, prompting officials who oversee the program to question whether it can function at all.

Related:

- From Sleeping Bear to North Country Trail, advocates fear worst from Trump cuts

- Michigan universities would lose millions if Trump caps research costs

- Michigan’s EV transition in limbo as Trump halts climate spending

The lamprey staff were among thousands of federal workers fired without warning over the past week, with more promised as President Donald Trump and his appointees target recently hired or promoted federal workers whose probationary status gives them few job protections.

Agencies affected range from the Environmental Protection Agency and US Forest Service to the departments of Veterans Affairs and Education.

Representatives of federal workers’ unions are still tallying the dismissals affecting Michigan, but they estimate it includes at least 60 employees of the Forest Service and up to 50 at the EPA’s Region 5 offices in Chicago, along with dozens to hundreds more in other agencies.

‘I’d like to ask them why’

Those knowledgeable about the firings in environmental and public lands agencies say the consequences will include dirtier bathrooms at national parks, slower replanting after logging in national forests, laxer oversight of corporate polluters, weaker responses to wildfires and fewer fish in the Great Lakes.

“I’d like to ask them why,” said Graham Peters, a 33-year-old Petoskey native who until last Friday worked as a forestry technician in the Hiawatha National Forest. “And if they understand what they’re doing. Because it doesn’t seem like they realize who they’re getting rid of, and the impact it’s going to have.”

Peters’ job included replanting forests with young saplings, and he said he put in “100% effort all the time.” Supervisors were apologetic when they called to fire him, explaining that his name was on a list handed down by the federal Office of Personnel Management.

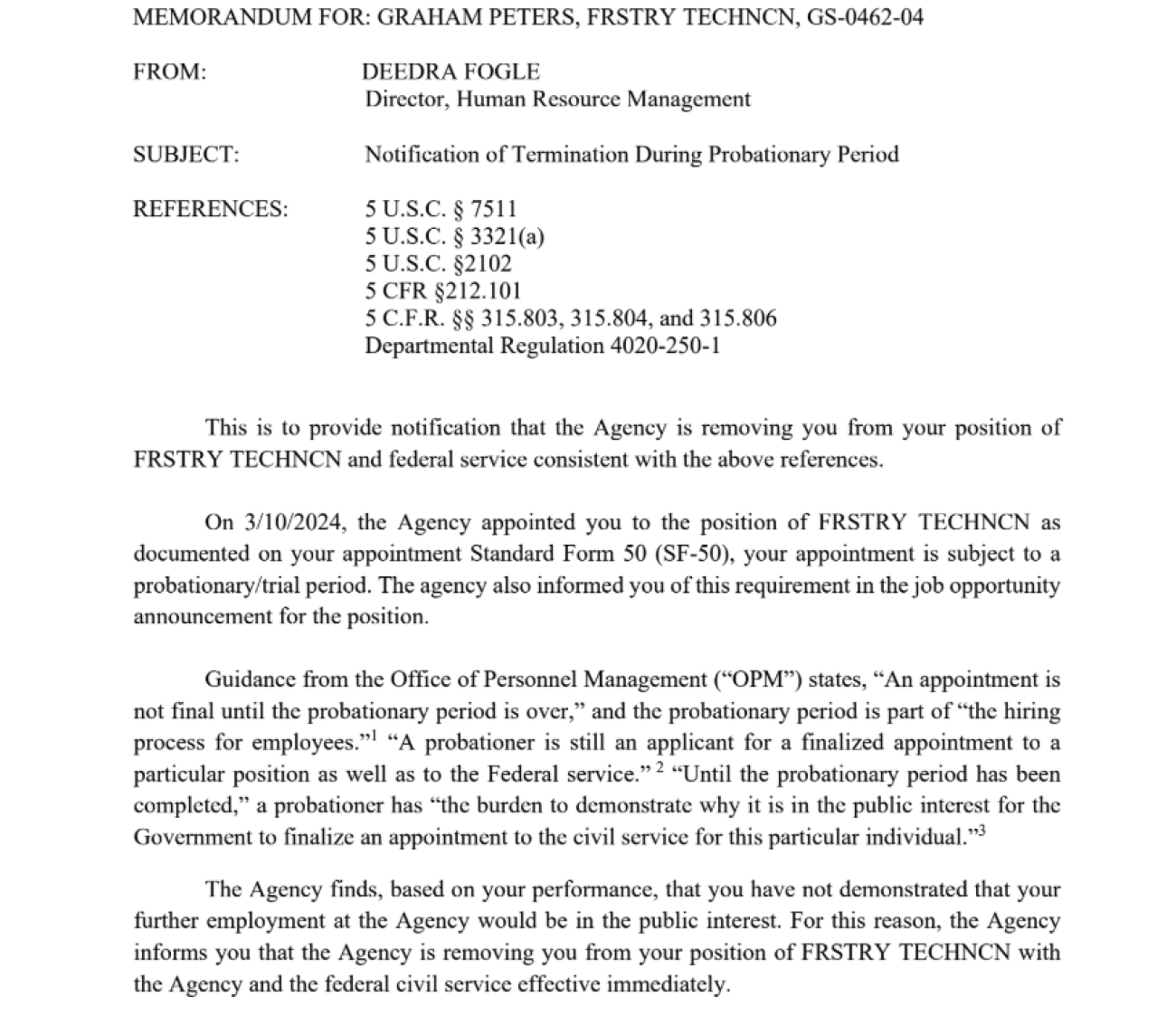

A follow-up letter contained the same terse message that was sent to at least four colleagues in Peters’ roughly 40-person office, and 3,400 workers across the Forest Service:

“The Agency finds, based on your performance, that you have not demonstrated that your further employment at the Agency would be in the public interest.”

Peters feels betrayed by politicians he helped put in office. He voted for Trump in November, impressed by his vows to bolster the economy and slow immigration across the southern border.

“If I had known that this was going to happen,” he said, “I wouldn't have voted for him.”

The White House has vowed to work with Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency to “significantly reduce the size of government,” arguing a glut of federal workers is driving up the national debt.

But with a salary of about $36,000, Peters wasn’t a highly paid bureaucrat. Neither was his colleague Emily Anderson, a wildlife technician who spent her days improving fish habitat and monitoring fish and wildlife populations. Anderson moved to the UP from New York state last year for what she hoped was a long career in fish and wildlife conservation.

But despite glowing reviews during her first 10 months on the job, she was fired Friday while preparing to gas up the snowmobile ahead of work on a frozen lake. Along with her termination letter, her manager mistakenly gave her a document that instructed supervisors on how to carry out the mass firings.

“It pretty much said show no emotion, show no fault. Just give them this termination letter and then have them return everything by the end of the day,” Anderson said.

Peters and Anderson were among about 17 Forest Service workers fired in the Hiawatha National Forest, plus about 40 in the Huron-Manistee National Forest and an unknown number in the Ottawa National Forest, said Warner Vanderheuel, a union representative for the National Federation of Federal Employees who works as a battalion chief firefighter in Huron-Manistee.

The administration vowed not to fire employees in public safety and firefighting positions, but Vanderheuel said firefighting capabilities will nonetheless be impacted because many employees working other positions are certified to fight fires when needed.

Other losses include office managers who coordinate logistics like food, gasoline, and lodging for crews deployed to forest fires, and wildlife technicians working on research and habitat restoration.

“These aren’t … quote-unquote bureaucrats,” Vanderheuel said. “They’re people who get their hands dirty and make sure the trails are cleared so you can ride your ATV. They clean your campgrounds. All the paint on the trees that people see? These are the guys and gals who paint the trees so we can sell timber.”

At the Environmental Protection Agency’s Region 5, which enforces federal pollution laws in Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota, Ohio and Wisconsin, about 100 people have been fired or resigned since Trump’s inauguration.

That’s roughly 10 percent of a staff that once numbered about 1,000, said Nicole Cantello, president of the American Federation of Government Employees Local 704, which represents EPA workers in the Great Lakes region.

“We lost like six attorneys who bring cases against environmental polluters,” Cantello said. “Having less of them means that the air will be dirtier and the water will be dirtier.”

‘It equals really bad’

Representatives from the Great Lakes Fishery Commission were in Washington, DC on Wednesday urging lawmakers to intervene in the cuts affecting lamprey control efforts.

“This simply puts us in a place where we don't know if we're able to actually run a program in the year ahead,” McClinchey said.

The program costs US taxpayers more than $20 million annually, and in return it protects a multibillion-dollar fishery from an eel-like invader that entered the Great Lakes on manmade shipping canals more than a century ago.

A single lamprey can consume 40 pounds of fish annually by attaching to the animals’ skin with razor-sharp teeth, slowly draining their fluids. The Great Lakes ecosystem was in collapse by 1957, when scientists discovered a chemical compound called TMF that kills lamprey while sparing other species.

Today, the fishery commission contracts with the Fish & Wildlife Service to dose hundreds of rivers with TMF each year. As a result, lamprey populations are down about 90% from historical averages. But recent history offers a window into the risk of a lapse in treatments.

During the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, the lamprey control program was scaled back by about 25% amid border closures and social distancing protocols. In some areas, lamprey populations tripled.

Skipping an entire treatment season would be unprecedented in the program’s seven-decade history. Some 4.5 million female lamprey would be allowed to survive and spawn, laying a combined total of 450 billion eggs.

“I can’t do that math off the top of my head,” McClinchey said, “but I think it equals really bad.”

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!